Technical Notes on ♥️ Bird

Inspired by the example of musicians like Jacob Shulman and Miles Okazaki sharing a peek into their compositional approach, I wanted to jot down some notes about <3 BIRD, my tribute to Charlie Parker released earlier this year.

Inspired by the example of musicians like Jacob Shulman and Miles Okazaki sharing a peek into their compositional approach, I wanted to jot down some notes about <3 BIRD, my tribute to Charlie Parker released earlier this year.1. Greenlit

Greenlit borrows its harmony from Parker’s early pioneering composition “Confirmation” and adds an oscillating metrical form and new melody. [this and other italicized excerpts are my one-sentence summaries from the liner notes]

In the course of my studying up on Bird during the pandemic, I was pretty shocked to learn that "Confirmation," which may be the most rhythmically and technically challenging standard bebop melody to learn due to its varied melodic shapes, abrupt changes in subdivision, and limited repetition, was among Bird's earliest-known compositions. He had it prepared to be recorded on a date with Dizzy Gillespie in February 1946, but in accordance with his legendary extra-musical inconsistency, he never made it to the date; the recording survives, with Lucky Thompson, Milt Jackson, Al Haig, Ray Brown, and Stan Levey.

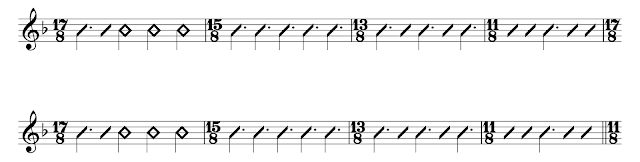

The harmonic momentum of the A sections is part of the draw for me and musicians before me, and I used that as a template to compose a "negative" or inverse harmonic progression that is the basis for "Transaccidentation," the opening track of my first album. For "Greenlit," I wanted to keep the original harmony while designing a new metrical obstacle course for myself; in the simplest terms, it starts in 11/8, then adds an eighth note every bar for the next four bars, then when it reaches 15/8, it goes in reverse, subtracting an eighth note until returning to 11/8 for the next A section.

On the bridge, there's an intended sense of release as it suddenly switches to a longer meter of 17/8, which is followed by a feeling of quickening pace as the following three bars lop off two eighth notes per bar (15/8, 13/8, 11/8). The four bars repeat this metrical cycle once more before returning to the last A, which begins on 11/8, the same meter as the last bar of B.

The inspiration for this mixed meter approach comes from Bird's unmatched flexibility of phrasing. Although he might have performed songs considered to be in 4/4 more or less his whole career, to my ears, Bird wasn't really playing in 4/4: the beginnings and endings of his phrases implied every kind of meter, so while the "container" for his music might be understood as 4/4, the way he filled it was a marvelous jigsaw puzzle of complementary and at times asymmetrical rhythmic phrases that somehow balanced one another in the end. To this point, I don't think Bird would have had much trouble navigating this kind of mixed meter context; like a cat that always lands on its feet, he always had a way of extending or contracting his phrases to make a specific musical point, and I imagine that he would have taken naturally to this sort of musical environment that embeds his flexible phrasing approach into the compositional framework itself.

The melody of the piece is a kind of circular breathing etude that exploits false fingerings on the saxophone to outline the metrical subdivisions. Adam O'Farrill did an amazing job of adapting various harmonics on the trumpet to phrase the melody, and I can't take any credit for specifying valve fingerings or anything like that; that was all him.

2. Adroitness, Part I

Adroitness is based on “Dexterity,” focusing on melody in Part I and on rhythm in Part II.

"Adroitness" is my take on "Dexterity," an elegant rhythm changes line that notably uses the sound of the major b6 to great effect. The melodic effect of this "negative dominant third" or borrowing from the minor mode is brought out by the first portion of the piece being taken at a slow tempo, with the melody split out between the treble and bass voices, played by clarinet and bass respectively (Rhodes doubles both voices). For pacing, the A section is only played once before immediately moving to the bridge, so the first part is a short and sweet ABA, with a twinkling sonority emerging from the blending of woody and electric timbres.

Below is how I split things up: the top line shows the original "Dexterity" melody for reference, while the lower two voices are how the treble and bass melodies pass back and forth the pitches from the reference (all sustains are removed for illustration purposes, as you can hear the actual performance has prominent sustains for harmonic effect). Generally, there is less doubling than there is one voice playing while the other sustains, but there is occasional doubling where it makes melodic sense for each voice.

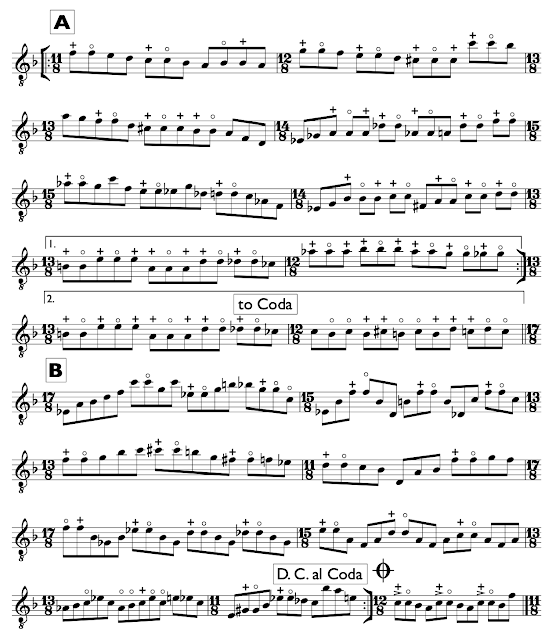

While "Part I" highlights the melodic line, "Part II" highlights the rhythmic accents within the line that make it come alive. As will become apparent in the notes to other songs on the album, this is not the only instance where I tried taking something originally in 4/4 and making it "not 4/4" through re-metering. Basically, I examined the original melody, highlighted where I felt the most notable accents were within the line, then extracted just those pitches in those rhythmic positions to create a "new" melody. Then, I redrew the barlines to reorient the downbeats around some of these major accents, or wherever it seemed reasonable or natural given the shape of this melody that was extracted out of the existing pitch sequence of "Dexterity."

Below is first part of the process described above, where the top line shows the A section of "Dexterity" with accents in 4/4, with the bottom line showing just the accented pitches (the "new" melody) in 4/4 and redrawn barlines shown as dotted barlines within the measure.

The point wasn't just to add complexity for its own sake, but to experiment and see what happens when you shift the placement of downbeats to follow the variously placed accents within a Bird line; to my ear, doing so makes the flow of time feel off-kilter in a pleasingly unsettled way—having a sense of forward momentum, but with an irregular and surprising texture that necessitates a different way of improvising together.

On to part II.

Comments

Post a Comment