Steans Sojourn: Eddie Harris, Don Byas, Other Apocrypha

|

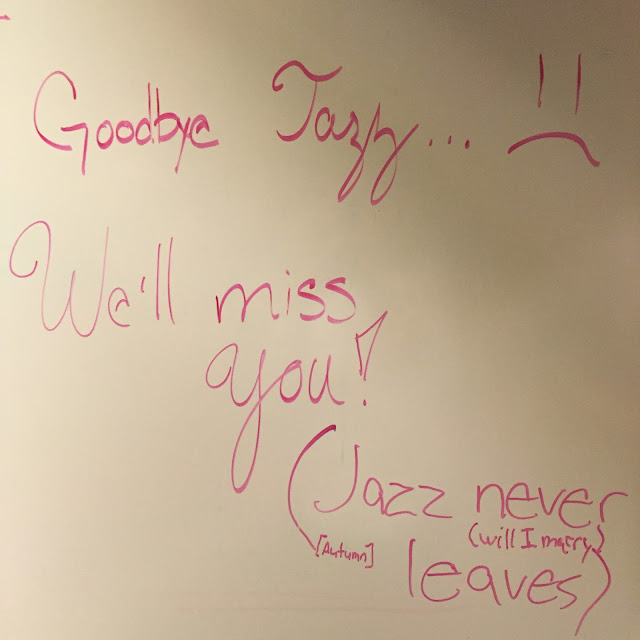

| Nested brackets and jazz tune titles — vestiges of jazz camp |

The ages ranged from 17 (!) to 30s, although the median age I'd guess would be somewhere around early-mid 20s, and I was amused to find that the accomplished level of musicianship didn't preclude some overtones of "jazz camp" (the resident ping pong table, dorm room hangs), which was a blast from the past for just about all of us.

To my pleasant surprise, Chicago-born saxophonist Eddie Harris, whose music and books (more on that later) have been a recently-blossoming interest of mine, emerged as a common thread through the program: Billy Childs had encountered Harris at a recording session back in the '90s; Nathan Davis knew Harris personally and recounted some two-tenor shows from back in the day; and Rufus Reid perhaps knew him best, having worked for a while in his band and recorded on such albums as Eddie Harris Sings the Blues, which I'd snapped up a few months back at Deep Thoughts JP.

Wisdom and anecdotes were generously disbursed on a daily basis. By the end of the week, we'd been impressed with the need to take caution when managing our own music and publishing; as Eddie Harris told Reid years ago, "Don't sell it. Own it," regarding his own copyrights, and Harris himself impressed Reid with the message by doing something "so righteous," to use Reid's words—Harris, after asking Reid to walk some bass lines for jazz pedagogical backing tracks, put both their names on the copyright, and decades later, Reid still gets an occasional check for royalties long after Harris passed on. Other sage advice from Harris via Reid, this on publishing your own books: "When your books collect dust, at least it's your dust" (this I'd call an "Eddie-ism," even if it didn't make it into Vol. 1-3 of Intervallistic Concept).

On the topic of bands' longevity, the Modern Jazz Quartet (which I've slept on for too long): each member of the band had distinct duties, and even though each member individually might not have had a reputation as being absolutely "the baddest cat"—shredding through changes, etc., although of course they were all bad—their concept and their chemistry made the band so happening and so steadily-working, not to mention so widely appreciated.

Workshopping original music with Reid was immensely gratifying; I used to listen to Anniversary! and Serenity, two live Getz records from the late '80s, on repeat in the car growing up, and I could still probably sing most of the solos from those records, including Reid's. Some of the footage from these concerts is even on YouTube.

I was probably least familiar with Nathan Davis's work before meeting him at Steans, where I realized I did know about him: I'd heard Woody Shaw III give a presentation at Harvard a couple months back where he'd shown photos of Woody and Davis playing together in Paris in the '60s, where they practiced and performed together for a time. In fact, it was Davis who introduced Woody to the music of Zoltan Kodaly and Bela Bartok. Now 78 and still playing with a huge sound on the tenor and a lush, Lucky Thompson-inspired sound on the soprano, Davis had countless stories to share.

He'd heard and met just about all the post-'40s great tenorists and could confirm who had the biggest sounds: #1 was Don Byas, who played on a Dolnet tenor saxophone with a massive tip opening and #5 reed (a.k.a. the "tongue-depressor," the hardest you can get); #2 is Sonny Rollins. As I'd suspected, both Eddie Harris and Joe Henderson had fairly small sounds (both played small Selmer tip openings, and I can hear a core-sound similarity in the two), but I didn't realize how many players used to "fix" their own mouthpieces: Dexter Gordon, Johnny Griffin, they all had tricks up their sleeve and worked on their mouthpieces in private, according to Davis.

It was a real privilege to meet all the cats last week, and I'm also grateful for the entire staff at Steans who shuttled us about every day and acted as guardians of order in what would have otherwise not been such a fertile environment for composition. One last note: the jazz program at Steans has been around for 14 years, and they've kept photos of past participants in the office. I was pleased to find some sincere, younger versions of artists I look up to in there; no photos for sharing, though; I know I wouldn't wish that on myself in 14 years.

Comments

Post a Comment