Mark Turner on "Head Trip"

I first wrote about "Head Trip," Aaron Goldberg's contrafact on "One Finger Snap" from his début release, Turning Point (1999), almost three years ago. Listening to this, it's revealing how much of the language Mark plays on this up-tempo, dominant-chord dominated tune is bebop (in particular what he plays over the concert Ab7 of each chorus right before the descending minor ii-Vs). Some of the other now-trademark Mark-isms are present in varying degrees—e.g., the almost ostentatious use of quarter motifs (first chorus), accordion-fold arpeggios (top of fifth chorus)—but there's notably minimal altissimo on this particular take.

Aaron has played with Mark since the early '90s, and was very generous in sharing his perceptions on Mark and the scenes they came up in. I ultimately only slipped in a brief quote in the finished piece in order to keep the length manageable and give everyone interviewed a chance to have their say, but here's more from Aaron on Mark:

We all grew up very much in the tradition, meaning we loved to play standards and we loved to swing and we spent many, many years studying the masters that came before, and Mark is a prime example of that ... he came to saxophone relatively late—took it up as a serious potential profession relatively late—but he’s a very disciplined and studious guy. He very immediately realized correctly that if he wanted to become a great saxophone player, he had to study the great saxophone players before him. I think he did it not merely because he had to, but because he loved to, so he totally immersed himself in John Coltrane, went through a period where he sounded very much like Coltrane, very much like Joe Henderson—and this was before we played together, but you could still hear those influences in his playing. And then he had a period of sounding very much like Warne Marsh, and you can really clearly hear Coltrane and Marsh in his sound—less so Joe, but you hear it in his sound and a certain kind of melodicism.

He has this tendency to balance a more cerebral approach with a purely melodic and emotional approach, so Mark himself is a combination of those two tendencies which are in us, but very pronounced: the warm and loving, soulful part of Mark, and there’s a more cerebral part of Mark, and there’s a spiritual part of Mark. He spends a lot of time studying Buddhism and meditating and doing yoga, and he’s a model for many of us for how to balance these different aspects of yourself. There’s the family side of him and the professional side of him. He’s always searching for that balance and finding it to differing degrees over the years.

Another relevant balance and maybe the one that explains why he’s so influential—perhaps the most influential saxophone player on other saxophone players since Branford, since the ’90s—is that he found a way to sound immediately, recognizably unique. In other words, like himself. Two notes and you know it’s Mark Turner—or 10 seconds of improvising, and yet he sounds completely grounded in the jazz tradition. He’s speaking a jazz language but in an accented kind of vocabulary that’s very much his own...

...We were talking about balancing different musical objects. Mark is somebody who has the ability to play extremely complex and sophisticated lines and melodic material in his solos, and one thing that separates him from many of his followers is that he also really knows how to play the shit out of a very simple melody. When you hear him play, for example, an original melody I wrote or somebody else wrote or his own tunes or just a standard, he knows how to state the melodies simply, and he knows all the melodies to all the standard tunes as saxophonists of older generations always did. He understands the balance between stating the melody as it was intended and written and then exploring the possibilities that emerge from that. There’s always an element of simplicity among the complexity that grounds his playing.

The thing that I’d say has changed the most is that he’s also rhythmically forceful now in a way that he was less so 20 years ago. He’s grooving and worked very consciously on making himself a rhythmic force in the band, not merely a melodic and sonic force. I think part of that comes with playing with Fly in a trio setting ... He’s worked a lot with a metronome and playing with grooves and worked on the rhythmic aspects of his playing to the point that they’re rock solid and equally impressive as the linear and melodic aspects.

Mark’s someone who’s always been aware of this idea that you grow not just by expanding your strengths, but also by working on your relative weaknesses; and he’s always been a very disciplined practicer and tried to do both. He’s always been expanding the capacity of what he can do and also strengthening the things that need to be strengthened that are potentially simpler. He’s always working in both directions at the same time, and that’s why he continues to get just better and better and better.

Classic things that jazz musicians have been expected to do over the years. like play a blues and swing; [it's] actually not a simple job at all to get very good at them, to get professionally and innovatively good at them. To command them is really not a simple matter. Mark is someone who has obviously embraced the possibility of complexity and expanded the harmonic and melodic vocabulary of jazz, and has also maintained his desire to just continue to get better at the more classic elements like playing standards and swinging and playing the blues. – Aaron Goldberg

C

Bb

Eb

Aaron has played with Mark since the early '90s, and was very generous in sharing his perceptions on Mark and the scenes they came up in. I ultimately only slipped in a brief quote in the finished piece in order to keep the length manageable and give everyone interviewed a chance to have their say, but here's more from Aaron on Mark:

We all grew up very much in the tradition, meaning we loved to play standards and we loved to swing and we spent many, many years studying the masters that came before, and Mark is a prime example of that ... he came to saxophone relatively late—took it up as a serious potential profession relatively late—but he’s a very disciplined and studious guy. He very immediately realized correctly that if he wanted to become a great saxophone player, he had to study the great saxophone players before him. I think he did it not merely because he had to, but because he loved to, so he totally immersed himself in John Coltrane, went through a period where he sounded very much like Coltrane, very much like Joe Henderson—and this was before we played together, but you could still hear those influences in his playing. And then he had a period of sounding very much like Warne Marsh, and you can really clearly hear Coltrane and Marsh in his sound—less so Joe, but you hear it in his sound and a certain kind of melodicism.

He has this tendency to balance a more cerebral approach with a purely melodic and emotional approach, so Mark himself is a combination of those two tendencies which are in us, but very pronounced: the warm and loving, soulful part of Mark, and there’s a more cerebral part of Mark, and there’s a spiritual part of Mark. He spends a lot of time studying Buddhism and meditating and doing yoga, and he’s a model for many of us for how to balance these different aspects of yourself. There’s the family side of him and the professional side of him. He’s always searching for that balance and finding it to differing degrees over the years.

Another relevant balance and maybe the one that explains why he’s so influential—perhaps the most influential saxophone player on other saxophone players since Branford, since the ’90s—is that he found a way to sound immediately, recognizably unique. In other words, like himself. Two notes and you know it’s Mark Turner—or 10 seconds of improvising, and yet he sounds completely grounded in the jazz tradition. He’s speaking a jazz language but in an accented kind of vocabulary that’s very much his own...

...We were talking about balancing different musical objects. Mark is somebody who has the ability to play extremely complex and sophisticated lines and melodic material in his solos, and one thing that separates him from many of his followers is that he also really knows how to play the shit out of a very simple melody. When you hear him play, for example, an original melody I wrote or somebody else wrote or his own tunes or just a standard, he knows how to state the melodies simply, and he knows all the melodies to all the standard tunes as saxophonists of older generations always did. He understands the balance between stating the melody as it was intended and written and then exploring the possibilities that emerge from that. There’s always an element of simplicity among the complexity that grounds his playing.

On comping for Mark:

He’s always harmonically stretching but hearing perfectly the original harmony of whatever he’s stretching over. His explorations always are aurally—not only theoretically—grounded to whatever the bass and the piano’s doing ... Mark allows you a choice of whether to stay grounded to what’s predicted, or try to follow him. It depends on your taste as an accompanist, depends on the situation. He’s always going to take you on a harmonic adventure, but it doesn’t mean you have to follow, because his harmonic adventure is predicated on the fact that you’re going to play what’s predicted and the relationship is always clear in his mind.

He’s going to sound good regardless of whether you stick to what’s there or you follow him. He’s never just trying something for the sake of trying something. There’s always a relationship being explored between what he’s interested in and what’s there, and it’s a very tight relationship, very logical, and also an aural-aesthetic relationship. He actually gives you a lot of freedom ... you have freedom as a comper whether you want to try to elaborate or you want to just hold your ground...

He’s going to sound good regardless of whether you stick to what’s there or you follow him. He’s never just trying something for the sake of trying something. There’s always a relationship being explored between what he’s interested in and what’s there, and it’s a very tight relationship, very logical, and also an aural-aesthetic relationship. He actually gives you a lot of freedom ... you have freedom as a comper whether you want to try to elaborate or you want to just hold your ground...

The evolution of Mark's playing over the years:

Mark’s someone who’s always been aware of this idea that you grow not just by expanding your strengths, but also by working on your relative weaknesses; and he’s always been a very disciplined practicer and tried to do both. He’s always been expanding the capacity of what he can do and also strengthening the things that need to be strengthened that are potentially simpler. He’s always working in both directions at the same time, and that’s why he continues to get just better and better and better.

Classic things that jazz musicians have been expected to do over the years. like play a blues and swing; [it's] actually not a simple job at all to get very good at them, to get professionally and innovatively good at them. To command them is really not a simple matter. Mark is someone who has obviously embraced the possibility of complexity and expanded the harmonic and melodic vocabulary of jazz, and has also maintained his desire to just continue to get better at the more classic elements like playing standards and swinging and playing the blues. – Aaron Goldberg

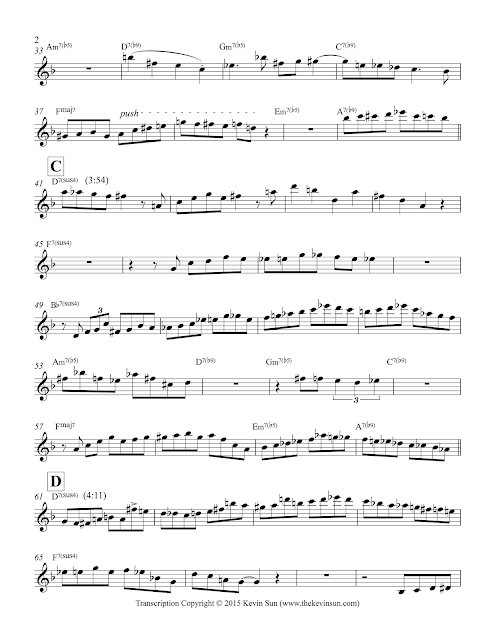

Solo transcription:

C

Bb

Eb

Comments

Post a Comment